Free speech for professionals?

In a boost for free speech the barristers' regulator has redrafted its social media guidance to recognise that free speech must prevail over the urge of the easily offended to cancel.

Professionals must be free to speak openly in a democracy, without fear or favour. But in recent years they have often fallen prey to regulators seeking to restrict what their members can say. The writer David Goodhart has noted that ‘the ethos of service and duty that used to underpin so many professions often seems to have been replaced with a claim to moral leadership by the better-educated.’[1] In pursuit of ‘moral leadership’ many professions have sought to discipline some of their members who have had the fortitude to speak out against prevailing orthodoxies.

Regulatory overreach

Most professional organisations require their members to not bring their profession into disrepute and whilst this obligation will normally relate to what professionals do in their professional lives it can extend to their non-professional lives. This is because the public expects high standards from their professionals. The public would rightly think it relevant if a surgeon or solicitor had stolen from a shop, even if he was scrupulous with his client account. But it is one thing to argue that a professional has brought the profession into disrepute if he commits a crime, it is quite another to stretch this obligation to cover what he may say on social media, especially if his commentary is political.

Regulators have tended to overreach themselves by, as Goodhart puts it, assuming that they must provide ‘moral leadership’. This is particularly so with issues much loved by the ‘better educated’ such as identity politics, climate change and other causes discussed in townhouses around Islington dinner tables. Those who challenge these nostrums of the right-thinking may well experience some regulatory heat.

This overreach by professional regulators is profoundly disturbing given the centrality of free speech to democracy. As the human rights court in Strasbourg put it nearly fifty years ago:

Freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of [a democratic society], one of the basic conditions for its progress and for the development of every man. Subject to [limited exceptions as set out in article 10(2) of the ECHR], it is applicable not only to 'information' or 'ideas' that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population. Such are the demands of that pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness without which there is no 'democratic society'.[2]

In a democracy professionals must have the same right to contribute to political issues as every other citizen. Indeed, since an independence of mind and an ability to tell it like it is are qualities that the professions should celebrate, the imposition of a right way of thinking is antithetical to the professional ethos. If there is one development that is most likely to undermine public confidence in a profession it is the public perception that professional competence has been compromised by political correctness.

BSB’s old guidance

The Bar Standards Board (BSB), which regulates the profession of barristers, has suffered from this tendency to put ‘moral leadership’ before its members’ right to speak freely. Drafted in October 2019 its social media guidance quickly became a charter for the easily offended to practise cancel culture, where denunciation prevails over debate. This guidance claimed that comments on social media ‘designed to demean or insult’ were likely to bring the profession into disrepute. Worse still, the guidance noted that ‘comments that you reasonably consider to be in good taste may be considered distasteful or offensive by others’. The implication being that objectively reasonable comments could bring the profession into disrepute if others subjectively considered them ‘distasteful or offensive’. And who hasn’t heard a (usually) left-wing campaigner say, as if it were the final word on a debate: ‘I find that offensive’?

Speech should never be curtailed on the basis of subjective belief, rather than objective assessment. If objectivity yields to subjectivity then political campaigners affecting hurt feelings will be empowered to chill debate. And if the yardstick is mere offensiveness then there is no shortage of political debates that will be skewed in favour of those who silence their opponents by championing the claims of the easily offended. As a corrective to this approach, it was stated in a recent court case that:

beliefs may well be profoundly offensive and even distressing to many others, but they are beliefs that are and must be tolerated in a pluralist society.[3]

Unsurprisingly, following the 2019 publication of the BSB’s social media guidance it received a significant increase in complaints about barristers’ non-professional lives. A BSB annual report for the year ending March 2021 found a significant increase in reports about barristers’ use of social media: from a mere two cases in the year ending 2017 to 49 in the year ending 2021.[4]

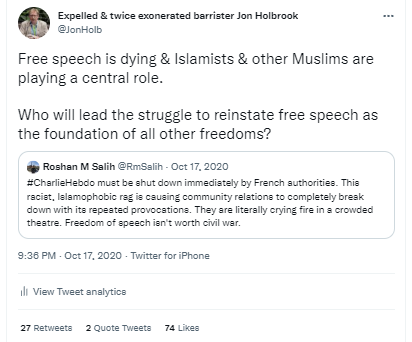

The low and inappropriate thresholds adopted by the BSB for asserting its claimed moral authority over the profession was typified by the BSB’s investigation of my social media. In January 2021 the BSB received 128 complaints about one of my tweets. These complainants, all of a certain left-wing political hue, often cited the BSB guidance before concluding with their assertion that I had ‘demeaned the profession’ with this tweet:

Of course, this was nonsense, but instead of triaging the complaints into the ‘NFA’ folder the BSB launched a formal investigation before reaching the obvious conclusion that I was merely expressing my ‘political opinion on a piece of legislation rather than intending to demean or insult another’.[5]

Worse was to follow when the BSB relied on its guidance to fine me £500 and issue a we-are-watching-you warning for this tweet:

In March, my appeal against this sanction was allowed and more importantly the tribunal concluded that the BSB’s social media guidance did not, for two reasons, accurately reflect the legal protection afforded to free speech. First, social media activity, which is not within the course of a professional’s practice, could only be impugned if it was conduct of a morally culpable or otherwise disgraceful kind which brought disgrace on the professional and thereby prejudices the reputation of the profession.[6]

Secondly, the legal right to freedom of expression is broad and particularly so in the context of political speech. Accordingly, curtailments of this right are to require high thresholds. The tribunal concluded that bringing the profession into disrepute requires:

something more than the mere causing of offence. At the very least, the relevant speech would have to be “seriously offensive” or “seriously discreditable” … Even in such cases there would have to be a close consideration of the facts to establish that the speech had gone beyond the wide latitude allowed for the expression of a political belief, particularly where the speech was delivered without any derogatory or abusive language and the objection was taken to the political belief or message being espoused, rather than the manner in which that belief or message was being delivered.[7]

BSB’s new guidance

The BSB should have withdrawn its unlawful guidance immediately, in response to this appeal decision. Four months later it has withdrawn it, although without mentioning the case of Jon Holbrook v Bar Standards Board, which made the withdrawal necessary.

The new Interim Social Media Guidance[8] differs in two important respects from the now discredited guidance of 2019. First, it does not suggest that subjectivity (‘I am offended’) can be a basis for regulatory action. Secondly, the objective thresholds for possible action are much higher. In place of ‘comments designed to demean or insult’ the thresholds now refer to comments that are seriously offensive, threatening, indecent, obscene, menacing or which are gratuitously abusive or which may incite violence.

The interim guidance is open for consultation until 20 October.[9] It can still be improved such as by removing the reference to comments that are ‘discriminatory’, a threshold that is so low and imprecise that it invites regulatory action against the barrister who expresses his view that ‘Liverpool are better than Everton’. However, the new interim guidance is a shot in the arm for free speech and indicates, hopefully, a desire by the BSB to not set itself up as moral guardians of a barrister’s political views. If so, that can only be good for barristers, the profession and democracy.

Jon Holbrook is a barrister

Follow him on Twitter: @JonHolb

His website is at: www.JonHolb.com

[1] Head, Hand & Heart: the struggle for dignity and status in the 21st century, David Goodhart, [2020] Allen Lane, p17.

[2] Handyside v UK (1979-80) 1 EHRR 737, §49, decision of the European Court of Human Rights, 7 December 1976.

[3] Forstater v CGD Europe [2022] ICR 1, EAT, §116.

[4] BSB Regulatory Decision-making, Annual Report 2020/21, §54.

[5] BSB decision of 9 August 2021, p1.

[6] Jon Holbrook v Bar Standards Board, The Bar Tribunal and Adjudication Services, 25 March 2022, §§50, 57.

[7] ibid, §44.

[8] BSB Interim Social Media Guidance, 21 July 2022.

[9] BSB Consultation on the regulation of non-professional conduct, July 2022.